The Effect of the Housing Bubble and the Role of Credit

A STUDY OF THE HOUSING PRICE BOOM IN SPAIN BETWEEN 1995 AND 2008 AND ITS COLLAPSE BETWEEN 2008 AND 2015 HIGHLIGHTS THE ROLE OF THE FINANCIAL SYSTEM AS A TRANSMISSION MECHANISM BETWEEN SECTORSby Tom Schmitz, Dept. of Economics, Bocconi

During the last decades, many countries experienced massive boom-bust cycles in house prices. Spain provides a good illustration for these episodes and their consequences. The spectacular 1995-2008 boom and 2008-2015 bust in Spanish house prices went hand in hand with an equally spectacular boom-bust cycle in real GDP. This suggests that bubbles have spillovers to the rest of the economy, for instance through the credit market. Indeed, Spain experienced a credit boom, and the share of construction and real estate in total firm credit increased from 22% in 1995 to 48% in 2007. However, it is not clear whether the massive expansion of housing firms reduced or increased the availability of credit for non-housing firms.

A priori, there are good reasons for both sides of the argument. On the one hand, the massive credit demand for housing may have crowded out credit from other sectors. On the other hand, higher house prices might also have stimulated credit in other sectors by providing collateral or attractive assets for securitization. In a recent paper with Alberto Martín and Enrique Moral-Benito, we argue that these views are not mutually exclusive, but describe two phases of the same phenomenon: housing bubbles initially crowd out credit from other sectors, but eventually – if they last long enough – crowd it in.

Our argument relies on a simple macroeconomic model in which banks and firms face financial constraints, meaning that the amount they can borrow depends on their current wealth. When a housing bubble appears, housing firms get wealthier and demand more bank credit. Banks cannot increase their credit supply, as the bubble does not immediately affect their wealth. Therefore, the bubble initially lowers credit to non-housing firms.

As long as the bubble lasts, however, housing firms repay their loans. This increases the banks’ wealth, enabling them to borrow more from abroad and to expand credit supply. This reverses the initial decline in non-housing credit and eventually even leads to its expansion. Finally, the collapse of the bubble lowers loan repayments to banks, triggering a general credit crunch.

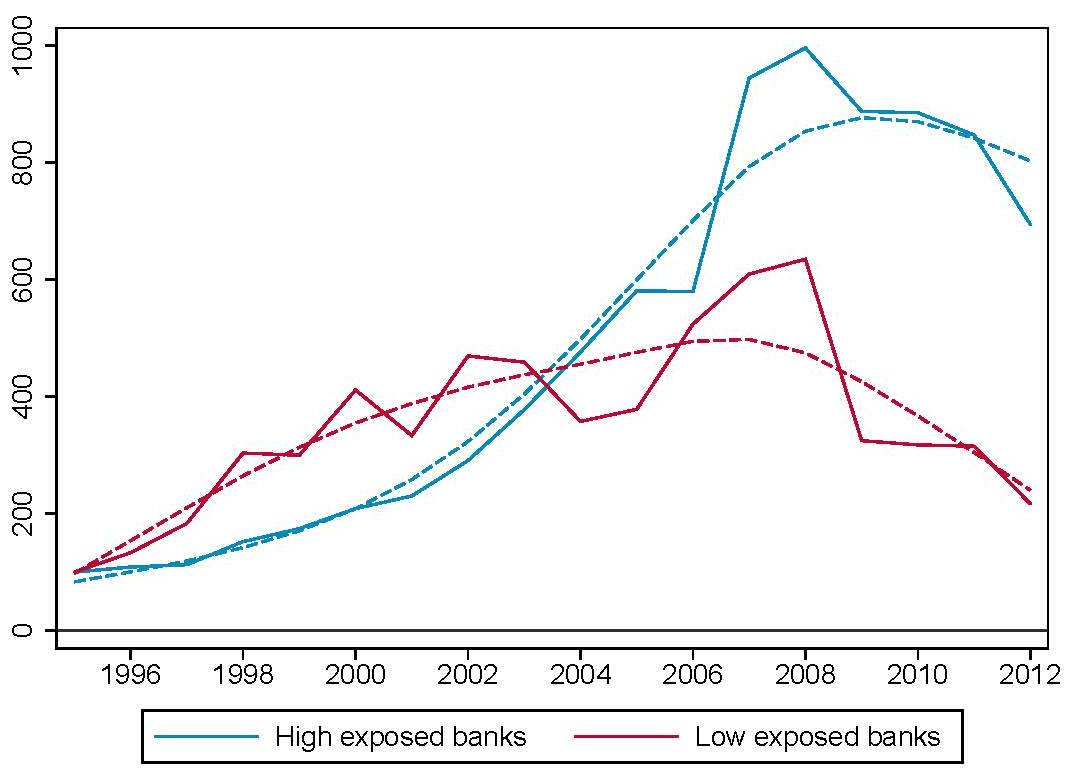

To show that these effects were at work in Spain, we use a dataset from the Spanish Central Bank that contains essentially all bank loans to firms. We note that some banks were more exposed to the bubble, having business models focused on housing or being located in regions with greater house price increases. Thus, non-housing credit should initially grow less at more exposed banks than at less exposed ones, but this pattern should reverse later. Figure I shows that this is indeed what happened.

Note: Total credit to non-housing firms (normalized to 100 in 1995) on the y-axis. Exposure is measured by the ratio of mortgage-backed credit to total credit before the start of the bubble. The Figure shows banks at the 10th and 90th percentile of this measure.

These results persist when controlling for systematic differences between clients of different banks, and extend to the firm level: firms borrowing from more exposed banks had initially lower credit growth, then higher credit growth in the last years of the bubble, and lower credit growth during the crisis. The same results hold for value added.

Summing up, our research suggests that concerns about housing bubbles absorbing credit needed in other sectors is likely to be temporary. However, the crowding-in effect of bubbles is also fragile, as bubbles can burst. Finally, our results generalize to other sector-specific shocks beyond bubbles, highlighting the role of the financial system as a transmission mechanism between sectors.

Note: The views expressed in this column are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the ECB or the Bank of Spain.